One for all and all for one: an introduction to online language learning communities

Introduction

“Learning is the engine of practice, and practice is the history of that learning”, is what Etienne Wenger wrote in his book ‘Communities of practice: learning, meaning and identity’. We’ve been fascinated with this phenomenon of people learning in a community by sharing and helping each other. Over the last couple of decades we’ve seen the Internet grow and its impact on society. It created a platform for creative people to share their interests, ideas and identities. Communities in this digital era were born. There exist lots of different online communities but we were interested in learning communities, especially for Japanese language learning. We were curious about what they do, what they provide and what the role of (popular) culture is.

Here we will discuss what an online language community entails. The concept community, learning community, online community and language learning community will be explained step by step. We opted for Etienne Wenger’s theory of ‘communities of practice’ to get more insight on the social phenomenon of a community. Thereafter we’ll give some more context on language, culture and thought to explain the difficulties of learning a language, especially in regards to Japanese. Secondly, we would like to give an overview of the resources used by online language learning communities. The usage of language apps and web 2.0 applications will be explained. After that we will discuss popular culture as a catalysator for Japanese language learning and that discuss language, as a carrier of culture and the internet as an enabler and supporter for pop culture. At the end, we would like to discuss our research on these phenomena. We tried to get a general overview on the Japanese learning apps used in this day and age. Google Play Store and Quora are the media we opted for. We’ll discuss the process, data, difficulties and outcome. We hope you’ll get an understanding of online language learning communities and the resources they use. Hopefully it’ll guide you on your own digital language learning journey.

Online Learning Community

As Rajesh Koothrappali from the Big Bang theory says in episode 16 from season 6 “We are a community, and as long as we have each other, we are never truly alone”. For the purpose of this research, let us start from this statement and dive deeper into what a community comprises.

Specifically, this is a ‘community of practice’, as defined by the educational theorist Etienne Wenger. At present the concept of communities of practice are often applied to online communities and the process known as Knowledge Management. “They are formed by people who engage in a process of collective learning in a shed of human endeavor”, as defined by Etienne Wenger and Beverly Trayner. They share the same interests, values, objectives… and start exchanging ideas.

Practice is the source of coherence of a community, this relation is defined by three dimensions: mutual engagement, a joint enterprise (common purpose) and a shared repertoire.

Mutual engagement exists because people engage in actions which are reciprocally negotiated by the members of the community. If one engages in negotiating, they become members of that community because it is not just a matter of social hierarchy or having a title. Mutual engagement creates relationships among people by having a shared practice.

A joint enterprise is the result of a collective process of negotiation, defined by the members/participants in the process of pursuing it and creates relations of mutual accountability among the participants. That means that to regulate communication, rules or codes have to be defined to organize the community, thus creating a community culture in which everyone has a distinctive role. This creates a sense of responsibility/mutual accountability, the feeling each member matters, and doing so it enhances the sense of belonging. Every human being wants to be ‘part of’ the group, feel secure and surrounded by people who share the same interests. In the context of a community we call this “sense of community”, and it’s a key element to the proper functioning of the group.

When members have a strong sense of belonging, they contribute and participate more efficiently in the group activities, furthering learner-to-learner communication. This is all the more important in learning communities, where the main purpose is to share/extend knowledge and serve educational needs without forgetting to mention that a learning process is not something we go through alone.

The last dimension is the shared repertoire. These are the resources that are created by the pursuit of a joint enterprise for negotiation. These are not mere symbols or artifacts but include words, ways of doing things, gestures, routines and concepts that the community has produced or adapted which have become part of its practice. “A learning community includes learning, not only as a matter of course in the history of its practice, but at the very core of its enterprise.” Wenger defines learning as evolving forms of mutual engagement, understanding and tuning the enterprise and developing a repertoire, style and discourses.

Teacher-student relation and motivation

In addition to the aforementioned elements, another specificity of learning communities is the crucial role of the teacher-student relation. Learning occurs when an individual interacts with its social environment, thus stating it is a group activity, but for the learning to be efficient we need a mentor that ‘already knows’. Someone who provides the learner with a secure space in which he/she can evolve, ask questions and most importantly get feedback. Learning from mistakes is known to be an effective way to improve as humans naturally don’t enjoy failing. Apart from feedback, the teacher (mentor) should provide the student (learner) support and encouragement to attain the end-goal. Understanding what the learner wants to achieve and, according to it, adapting the teaching method and contents are critical to the learner’s learning experience which then influences his motivation whether to continue or not. In other words, the teacher has to be flexible towards each individual learner and support him/her towards the objective. Learning and teaching are not inherently linked. Teaching does not cause learning but the educational instruction creates a context in which learning takes place. Teachers and educational material become resources for learning.

Another essential for the student’s motivation is his actual learning perception. When you can see your own progress it boosts your self-confidence and encourages you to continue/do better. Whether or not a student can perceive his progress often depends on the contents/materials proposed by the teacher. Therefore, the teacher should select contents that are usable in the situations the learner most probably will find himself in later. Another way may be to use the learner’s own experiences and incorporate them into the learning process, closing the gap between theory and reality which facilitates the processing of information due to the association with something familiar. Doing so the learning communities also train the learners critical thinking and reflective skills.

Online communities

To go even more specific we are looking into Online Language Learning Communities. Overall they work the same way as explained above, but have a few differences, bringing pros and cons into the discussion. Since it is online, it benefits from the fact that it has easy access, provides rapid communication between members and the possibility to instantly share a variety of contents including video and audio. But when it comes to the actual ‘language learning’ aspect, online isn’t always a good alternative. Because it is online, it’s harder to create the community culture and sense of community that is important for the learning process. If roles aren’t strictly defined, it’s difficult to maintain mutual respect, creating an unsecure environment, leading to non-efficient learning. Furthermore, the fact it is online means there is no guarantee of a teacher/mentor figure to be present in the community. To counter this you may point out the fact that online learning creates opportunities to talk with natives which is certainly true and helpful in the learning process. But we can’t negate the fact that natives often lack in-depth knowledge about grammar which forms the very basis of a language.

When we try to apply Wenger’s theory, in this case we can see that the common purpose usually consists of acquiring the ability to communicate in a foreign language and getting insight into an unknown culture. The participants can share their own experiences of learning a language, ideas, advice and methods through the Internet. They use all sorts of media like forums, chatrooms, (private) social media groups, apps et cetera. These methods and motivation will be explained in the following parts.

Conclusion

In Online language learning communities, two (or more) languages, thus cultures, have to interact with each other, often causing some misunderstandings from both ends. These conflicts can be recognized through the differences in how learners and natives reason and express themselves in very divergent ways. This might discourage the learner to actually make use of the opportunity to speak with natives resulting in a situation where the learner applies its own cultural background to the new language he is learning. We then can note learners make structural and grammatical mistakes or even word choices that sound odd to a native speaker.

Language, culture and thought in perspective

When learning a language, it’s not all about vocabulary and grammar but it includes non-verbal communication. This is all the more important for Japanese language learning as these non-expressed elements are more frequent in the Japanese language. Misunderstandings often occur when such non-verbal elements are misread or misused. To avoid miscommunication during the early learning process we should consider the following.

The Loop

Language is an ever ongoing construction which is used to express oneself. Even without talking, when we experience things and reason, we use language in our thoughts. Furthermore, thought is being influenced by our cultural background and the environment in which we live. Take for example not-translatable words: they express something from their culture/environment that is unknown to another. To put it in other words, language provides a frame in which individuals can express themselves and their culture, but this occurs within the context of a social environment which also forms and influences language. This contributes to identity-formation and this loop of mutual influence evolves together with society as values and laws change overtime, creating new words and letting go of others. To quickly illustrate this we don’t have to look far: the corona-situation is creating a new culture in which masks are mandatory, rules are changing and new words are being invented.

The question that should be considered is how we can improve language learning within this multi-cultural context. First of all, as noted in the previous section, language learning is a group activity that needs contact and interaction with not only a community but also the community that speaks the language (=natives). Language should be taught in combination with basic cultural aspects, including some of the non-verbal factors, to avoid early misunderstandings and promote intercultural communication between learner and native. By combining culture and language, and studying them in parallel you will not only get a better insight and more easily integrate yourself in this new culture, but this will enable you to expand your own worldview and enrich your personal identity-construction.

Culture through popular culture

We think some of those basic cultural elements could be introduced easily through the Japanese popular culture. Note that we, here at KU Leuven, use a series called Yan-san not only to develop our listening skills but also to get familiar with the Japanese culture. We also watched documentaries (Japanology Plus) to get, again, more insight into Japanese culture and customs. We are convinced learners could get familiar with Japanese culture by also using popular culture like anime, j-pop and so on. It does not mean the learner will be able to speak Japanese after watching or hearing hundreds of episodes/songs, but he will start to recognize passively certain aspects of both language and culture. Anime also tells stories often taking place in Japan and, if you take Kimi no na wa as an example, the rendering of Tokyo is pretty close to how Tokyo actually looks like. This is only to prove that if you choose your shows wisely you can get an accurate glimpse of what life in Japan might entail and the culture that goes with it. Of course this doesn’t provide all the necessary knowledge to master a language but it’s a fun and easy way that can work as an introduction to the learning journey.

For those who might be interested in reading a more developed example of how japanese popular culture can introduce Japanese culture, this blog article compares real Buddha sculptures to a statue from the famous anime called Naruto.

Grammar and Kanji

Another way to get a better understanding of the culture is the in-depth study of grammar. Grammar can be considered as a reflection of thought patterns which, as we established above, form identity and are a part of the mutual-influence-loop. Also noted in the previous section, this is where a first problem occurs within the context of online language learning communities because they don’t guarantee a teacher who possesses this in-depth knowledge.

Also specific to the Japanese language learning is the importance of not only grammar but also kanji as a base element to construct language knowledge. This is a very different way of writing that is unique to Japanese (originally coming from China) and should be emphasized on from the very beginning of the learning process. To study hiragana, katakana and kanji, some video games have been developed but keep in mind that whether you study it the ‘fun way’ or by the books, it demands effort and time investment. This brings us to the last point of importance: consistency. You can make the learning process more attractive by using ‘unconventional’ methods, making use of online communities, mobile apps as tools and so on, but always keep in mind it is a slow and long process you have to work through on a regular basis. Only then will you be rewarded by acquiring this new language alongside the stimulation of your personal growth.

Conclusion

Online learning communities and mobile apps provide an easy access environment and useful tools to the learner, helping him get started on his language learning journey, but when the learner wants to attain the higher levels, nothing will be more effective than enculturation. Take the example of how babies learn their mother tongue: they have no other choice but to try and express themselves to get what they want. So should the learner at some point be engulfed in the culture and society in which the language is spoken so he has no other choices but to use the language and improve to be understood.

Online media and resources

With the rise of phones in the 2000’s came an evolution in technology for smartphones. This meant that phones got better features, screens etc. as time went by. Phones also started to become able to do and teach things you needed real humans for before, including teaching languages through applications. A real turning point in the development of apps was the creation of the iPhone in 2007, and from then on phones started becoming “mini-computers'', with bigger, high-resolution screens, faster functioning, touchscreen, better clarity and even WIFI and 4G.

Evolution of Apps

With the Apple and Android App Stores coming into the picture, lots of apps started becoming popular, including language learning apps. As technology evolves, apps that were developed more recently can provide more intelligent features, since they have the qualities of more recent hard- and software. Popular language apps also keep making updates to answer to more recent technology and provide better language learning features. An example of this is Duolingo, which started as a basic English language learning app in 2011, but gradually kept updating features and now enables users for 106 different language courses to rehearse real-time conversations and keep up with streaks of days in a row using the app. Another feature that is rising in language learning apps is the usage of international communities, as a link between the app and the web of users. More and more apps enable users to talk to native speakers online, asking questions or practicing conversational skills, or to talk to other users learning the same language, sharing their experiences or hardships. This has the effect of more apps becoming online learning communities.

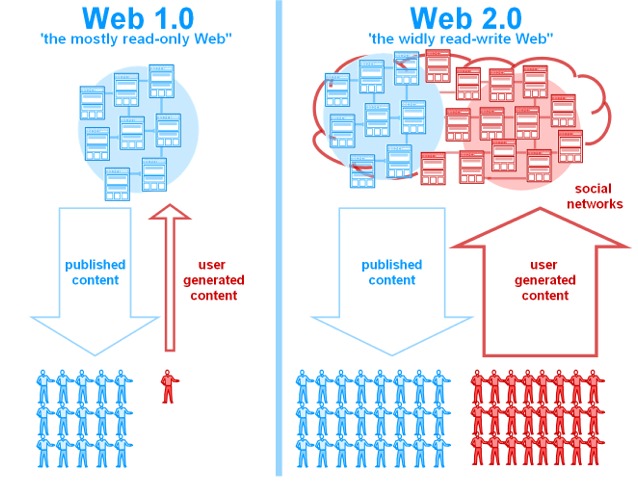

An interesting concept here is the so named “Web 2.0”. Web 2.0 refers to a range of sites that allow users to actively participate in the website’s content. This can be for example talk to other users, or share blog posts or messages yourself. Examples of Web 2.0 sites are Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, who allow users to post their own messages and comment on other users posts. In a way, this type of Web 2.0 sites make online learning communities possible, being people interacting with each other to learn languages, and the change from Web 1.0 (more passive content on websites) to Web 2.0 can make language learning online more accessible and interesting.

Image: Web 1.0 VS Web 2.0 VS Web 3.0

App Categories

You can find a wide range of apps for your phone that provide learning Japanese. These can be divided in a few categories.

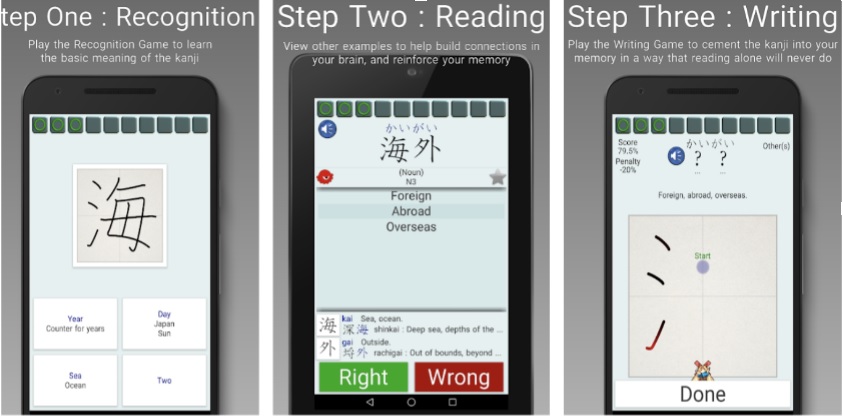

First, there are language learning apps that provide not only Japanese, but a variety of languages to learn on the same app. Examples of this category are Duolingo, Rosetta Stone and Lingodeer. As these apps allow you to learn multiple languages at once, often the same method is used for learning Japanese as for other languages like English or Spanish. The disadvantage to this is the lack of teaching specific alphabets (for example the kanji’s in Japanese), since the app was at first targeted at users that already know the English alphabet from their language learning English. Therefore, it can sometimes be better to switch to the next category, apps targeting learners of one language (for example Obenkyo and Kanji Tree), but since these are more specific, they are often less represented or not as developed as for example Duolingo. In this category there are apps for grammar and vocabulary, but also apps specifically for learning the hiragana, katakana and kanji that are often forgotten in apps targeting multiple language learning users.

Image: “Japanese Kanji Tree” https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.asji.kanjitree&hl=en

Another category are the flashcards apps, like Anki for example, that allow you to practice vocabulary or kanji for example by using digital flashcards. Duolingo even has its own flashcard app, Tinycards, as a complement to the original Duolingo app.

A fourth category is the dual language dictionary apps, as a replacement for physical dictionaries or dictionary sites. This can also be a site developed into an application, Google Translate for example, to make it easier to save translations and set personal preferences on the app.

The fifth category is not really a language learning app category, but more of an extension to learning languages by listening. Apps used to watch anime and Japanese dramas are starting to develop features to more actively learn a language by consuming popular culture. Viki for example is a website turned into an application to watch Japanese dramas, and recently they added a “learning mode” button, showing Japanese and English subtitles at once. When you tap on a word from the Japanese subtitles, you can also see a complete analysis of the word, including grammatical form. As Viki calls it “Edutainment” on their site, this aims for a combination of education and entertainment that might make fans of the popular culture automatically interested in learning the language too. This is also a perfect example of Web 2.0, since all subtitles and language learning tools are put on the site by users themselves, in other words helping other users learn a language as a community. A downside to this is that, because it’s provided by other users who don’t get paid, you often see shows with only half the subtitles, or the learning mode only available for the first episode.

Image:Kotobites

Popular series and movies watching site Netflix also has a language learning extension to see both subtitles, but this is not developed yet on the application, only made available as an extension to Google Chrome. A difference can also be seen in apps that are free and apps that are not. Most apps are free for basic features, but have options that require a single payment or a subscription with recurring payments. This could have the advantage of having no advertisements in between language exercises or games or being able to learn more words than free users. Sometimes even a limit is posed on the amount of time or games free users can play, allowing paying users to spend more time on the app. As you look through these different categories of apps, you can see none of them on their own have everything that’s required to fully learn to comprehend a language, but when you combine these different categories of apps, the user should be able to practice different aspects of language learning.

Advantages and Disadvantages

These applications have a lot of advantages, but disadvantages as well. Advantages include for example as said the continuous improvement of the system and the variety of language learning app categories. Another advantage is the fact that because apps are generated by a digital computer, errors are easier to detect, also when you repeatedly make the same mistake. A downside to this is that when there is a problem with the system, errors are not detected at all. Also a plus is the ability of apps to analyze a user’s personal improvement or mistakes. Because your app use is fully seen through the app's mind and every mistake you make is seen, you often can get more personal feedback than a real teacher can give you. A last advantage is time management. You can fully choose yourself when you study or how much time you study. This can also mean that studying is easily forgotten, but for this apps also have remedies, for example the loss of a streak of days you learned by not playing for one day. A disadvantage to apps is that none of them meet the complete requirements needed to fully learn a language. Most applications focus on vocabulary training, and the few apps that do focus on speaking, writing or reading, are not on the same level as classes in real life. Apps can also take a lot of internal memory, often making students decide to delete it in the end. A last disadvantage is, as previously mentioned, that with apps providing multiple languages to learn, the specific characteristics of Japanese are forgotten, thinking that all languages can be taught the same way that English is taught. This can be seen for example with Duolingo not focusing enough on kanjis, while this is a basic step for learning Japanese.

Conclusion

Studies have been done to research the place of language learning apps in university courses learning Japanese, and these mostly concluded that it can be a nice extension of the language learning process, but can in the end not replace real teachers. Until a certain degree, some classes or aspects of learning (for example vocabulary training) can be replaced by apps, but especially for grammar, reading and writing you will still need an actual teacher.

Japanese popular culture and Japanese language learning

From amateurs to experts

Albeit anime, manga, maid cafés, breathtaking actors, or talented singers, one aspect of Japanese popular culture or another has brought you here. In fact a significant percentage of first year Japanology students at KU Leuven found their choice of study major to be heavily influenced by what we call “Japanese popular culture”.

It should be noted that understanding Japanese is not a necessary skill to consume and to enjoy Japanese cultural products as there often are translations available. But a real insider knows very well, that translated content can only bring you this far. Unless you only want to scratch the surface of what is the black hole of Japanese pop culture, you need an extensive understanding of the language in order to further deepen your knowledge about the culture.

Medium

The two main media contributing to our research are language, as carrier of culture and the internet as enabler and supporter for pop culture. On the one hand, language as a building block, is necessary to understand how a society works and to contextualize human behavior. On the other hand, the internet is the place where language and culture come together in the form of music, games, and language learning applications, etc.

A concrete example of where language learning and culture meet is Dragon Tale, a game application to learn kanji with a storyline about Japanese mythology that introduces the user to mythical creatures and ancient tales in an educational, interactive manner. The mobile app consists of mini games that lets the user train on stroke order, meaning, pronunciation and explains compound words.

Image: Plecher, David A., Christian Eichhorn, Janosch Kindl, Stefan Kreisig, Monika Wintergerst, and Gudrun Klinker. 2018. “Dragon Tale - A Serious Game for Learning Japanese Kanji.” In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play Companion Extended Abstracts, 577–83. Melbourne VIC Australia: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3270316.3271536.

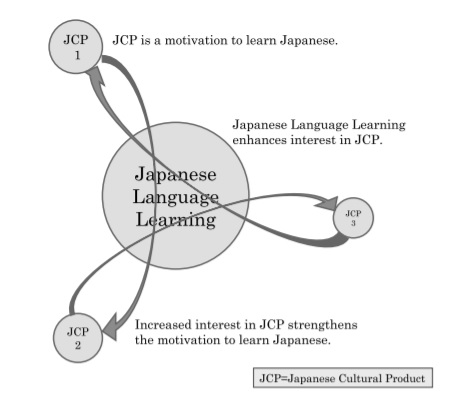

The cycle

A study done by Toshima Noboru shows that Japanese cultural products are the catalysator for Japanese language learning as 68.1% of students from his research started learning Japanese because of the liking they took to Japanese cultural products. Results of the questionnaire show that even though interest for Japanese media was the initial spark, expanding their knowledge of Japanese led to more consumption of Japanese media and newly found interests in other Japanese subcultures. The newly acquired cultural understanding, as language adds context to cultural practices, further motivated the students to keep learning the language. The study concluded that even though Japanese cultural products are the spark that ignites the fire of Japanese language learning, finding new Japanese cultural products is what pushes the students to further learn the language leading to continuous new sources to keep the students motivated to learn which ultimately makes them successful at mastering the language.

Image: Toyoshima, Noboru. 2013. “Emergent Processes of Language Acquisition: Japanese Language Learning and the Consumption of Japanese Cultural Products in Thailand.” Southeast Asian Studies 2 (2): 285–321. https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.2.2_285.

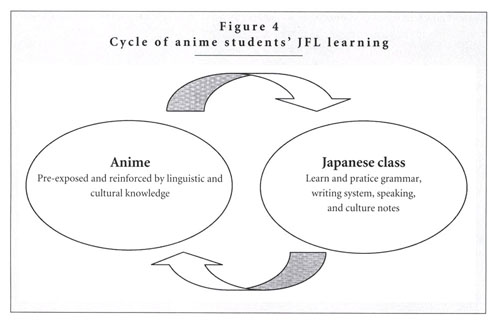

Image: Natsuki Fukunaga. 2006. “‘Those Anime Students’: Foreign Language Literacy Development through Japanese Popular Culture.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 50 (3): 206–22. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.50.3.5

Another interview study done by Natsuki Fukunaga on intermediate level, Japanese learning college-students who had an affinity for anime came to a similar conclusion (see illustration above). The study defines anime as an umbrella term for a multitude of subcultures such as manga, anime music and products (ex. merchandise), anime related activities such as cosplay, conventions and internet communities and games. The author’s data suggest that anime touches upon three linguistic aspects: word recognition, listening and pronunciation and finally awareness of Japanese linguistic features. These three features are the building blocks of the cycle and they also reinforce the link between language learning and popular culture. Watching anime provides a context for the words learned in class and at the same time during class students learn words they see in anime. Moreover, watching anime supplements the student’s knowledge of Japanese by making students used to hearing differences in speech according to the situation (普通体、丁寧態、敬語) and helping them understand gendered language usage (ex. ぼくVS私) and contextual (cultural) meanings of text. It can also lead to the discovery of other subcultures making the process a continuous loop.

Motivation

A study done by Nemoto Aiko concluded that students’ choice for Japanese was determined by personal experience and they started learning the Japanese language in order to overcome barriers they found while exploring Japanese culture. However, she nuances her research by stating that pop culture is merely an opportunity to develop interest in language and that other factors should be taken into account. Contact with Japanese pop culture alone is insufficient motivation to learn the Japanese language on more than a superficial level and pop culture is not necessarily the one and only motivator.

As shown by a study done in Hong Kong , cultural proximity is a significant factor for the spread of Japanese culture and cultural products, and consequently a motivator to learn the language. Consuming media and products from culturally similar countries is encouraged due to similarities in values, food culture, history, and pop culture. Similarities in language also seemed to play a noticeable role since 14% of students learned Japanese because they were familiar with Kanji due to Chinese writing system, as shown by a 2011 survey. Despite the influence of said cultural proximity, the study shows that it is not the main motivator for the study of Japanese.

Cultural attraction seems to be the number one reason for the popularity of Japanese language among Hong Kong students as shown by a 2011 email survey. Pop culture (including terms such as J-pop, idols, actors, drama, movies, make-up, etc), was chosen by the majority (76%) as the main reason for learning Japanese, closely followed by the language itself (59.3%) and lastly food and other reasons such as job opportunities (38.9%). Scholars suggest that interest in Japanese products stimulates language learning, making Japan’s soft power -culture and cultural products- the most influential motivational factor.

Not only that, but when asking students learning additional foreign languages to specify their reasons for studying that language, unlike their motivation to study Japanese, their motivations for other languages were unrelated to that foreign country’s cultural products.

Conclusion

Although not a necessity, multiple sources show that fans of Japanese pop culture are likely to want to or to engage in learning Japanese. The ones who do endeavor into learning Japanese more often than not end up in the continuous loop of learning and consuming pop culture.

Research

In this part of our research in language communities on online learning apps, we took a more standard approach by making our objective a general overview of the Japanese learning apps. The purpose was to use the Google Play Store and Quora as a means to acquire reviews about learning apps. These reviews can afterwards be analyzed by a text analyzing program combined with parameters that could arrange each comment by different apps. Finally, it was in our intentions to use the program called “tableau” to make conclusions on the extracted data. The following text will be explained in 3 parts, on the one side, the scraping of the Google Play Store, and on the other side the scraping of Quora, ending with our conclusion. This chapter will discuss the data we extracted and how we did it, the problems we encountered and how we dealt with it and end with the conclusion of this part of our project.

Google Play Store

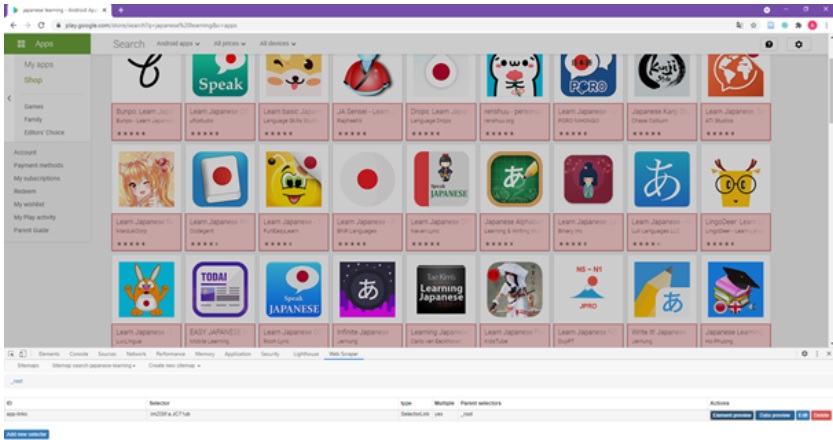

To get to know more about why, for what reasons, and what kind of functions people who learn Japanese find useful in an app, we used a simple search query in the Google Play Store: “Japanese learning”. From the results of this query, we selected the first 50 apps showing up after using the search query, which are a variety of Japanese-specific language learning apps, such as Obenkyo, and more general language learning apps, such as Duolingo. From the pages of these apps, the general information, the amount of downloads and the reviews were scraped using the browser extension “Webscraper”. The scraped data was later cleaned using OpenRefine. To analyze the text, Voyant Tools and MonkeyLearn were used.

Web Scraping

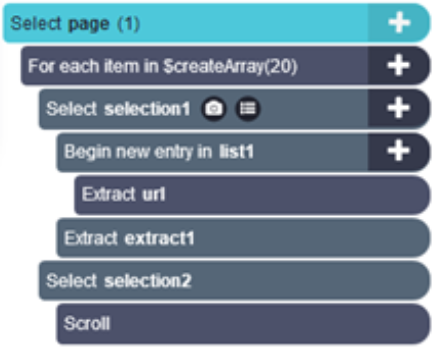

As stated before, for the scraping process, the browser extension “Webscraper” was used. We will shortly explain with screenshots how this was done. The process took some time to find out how a web scraper works, but after several hours of trying, this was the result we got out of it.

First, we used the search query “Japanese learning”. From the results, the links to the 50 first apps were selected by clicking the name of the app.

Afterwards, the info of the app and the amount of downloads the app has were selected as simple text (here named app-downloads-text & app-info-text). To select the reviews this was a different process: first, a ‘click element’ (here named app-reviews-selector) was used to select the part of the reviews that was shown on the main page, where only four reviews are shown, so this could later redirect to ‘Read All Reviews’ to be able to scrape multiple reviews in full (using app-reviews-text).

Finally, we were able to scrape all the reviews per app and exported it to a CSV file. This data was later cleaned using OpenRefine, to remove unnecessary text which was included, such as “UnhelpfulSpamLink to this review”; not cleaning this would disturb the data analysis process.

Data analysis

For the data analysis, Voyant Tools was mainly used for the main text analysis, while MonkeyLearn was used as a try-out add-on, as it seemed to have some interesting features.

First of all, apps providing multiple languages were, unsurprisingly, more popular than Japanese-specific apps. While the most popular Japanese-specific language learning app had more than 1 million downloads, the least popular app providing multiple languages (out of the ones researched), had more than 5 million downloads. However, this did not mean the Japanese-specific apps were less positively rated; all of the 50 scraped apps had an average score of 4 or more stars out of 5. Therefore it is also difficult to tell which apps are “bad” as none of the researched apps had a bad score (despite some apps having some negative reviews, but statistically these could be considered as outliers, being far away from the general point of view). This does not mean there are no “bad” apps out there, but this might be a weakness of selecting the first 50 apps, as the Google Play Store usually wants to show you the best and most relevant apps first.

From the text analysis of the reviews, the most common relevant word was kanji. This seems to suggest that people learning Japanese with these apps, are either happy with the fact that these apps teach you kanji, or that those apps do not have enough options to study kanji. Further analysis showed that the majority of people appreciated the functions in relation to kanji that the apps provided and even recommended extra features. Using a function in MonkeyLearn, which analysed the sentiment of the reviews which included the word kanji, confirmed that these reviews were positive. Furthermore, looking at the word frequency list in Voyant Tools, words with a positive connotation (e.g. good, great) appeared a lot more frequently than words with a negative connotation (e.g. bad), again confirming all apps were generally positively rated, as stated before.

Conclusion

The Google Play Store scraping process did not go quickly, however there were no problems with the results we got from the scraping. We concluded that the Google Play Store is good to look for apps to start learning Japanese. It is simple to find good apps, as the most popular and best rated apps always show up first. If someone would really want to try to study Japanese, one should try out a Japanese-specific app as these apps seem to offer more specific details on how to write in Japanese, such as kanji. However, our text analysis research did not go a lot deeper into this, due to lack of time after the scraping and cleaning process took longer than expected. We would have liked to visualise the data as well but this was unfortunately also not possible anymore due to the lack of time.

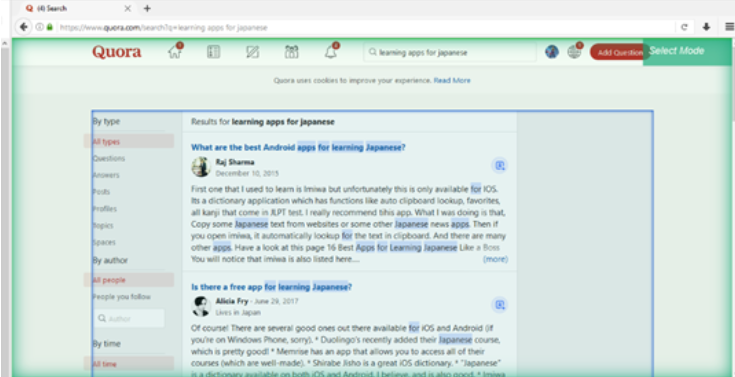

Quora

Purpose

Quora is a site where anyone can ask any question they want, whether it be a question about the weather tomorrow or the most intricate mathematical question ever. This means that people will supposedly ask questions about different language learning applications that would be answered by people giving their review on how good or bad their experience was and which application they recommend. With this in mind, we started typing keywords associated with our topic; for example “learning apps for Japanese”. This gave us a whole lot of results with different question that all could all be converted to same, main questions: “Is name of application good for learning Japanese” or “which learning application is the best for learning Japanese?. We expected these reviews would contain key-words such as “good”, “bad”, “lovely”, “easy”, etc. which could later be used by the text analyzing program. So, the purpose was to make a scraper that could get each and every question’s URL. Then collecting all the answers of every question, of which the number can vary from question to question, and finally analyzing these answers to make conclusions.

Extracted data + problems

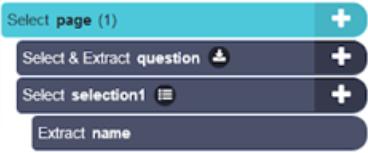

The program we used for this part is called “ParseHub''. It is a beginner friendly scraping program and is connected to the official “ParseHub” YouTube channel which contains a whole lot of explanation videos on how to work with the program. For the first step (collecting the URLs of the questions), there were 2 methods; first collecting the URL’s apart from the rest of the scraper or secondly, making the scraper click on every URL and include the rest of the scraper that would catch every answer. This will become clear later on.

First method

In this case we had to make 2 scrapers. One for collecting each URL and another one for collecting the answers on every URL. To collect every URL, the following scraper was used, this caused no problems and did his job perfectly

Explanation of the above scraper:

- Selects the webpage you want to scrape.

- Is a loop command which will repeat all the commands in the boxes within this command any number of times you specify. In the brackets of $createArray() is the number of times the loop will repeat.

- Selects the item you want to scrape

- Begins a new “mini scraper” within a selection

- Extracts only text (in this case we renamed it URL because that is the text it extracted)

- Ends number 4 by extracting all what we want from the above

- For this one we select the box in which the “infinite” scroll works (see photo below, the blue square is the selection we made for the scroll)

- Will scroll in the selected box

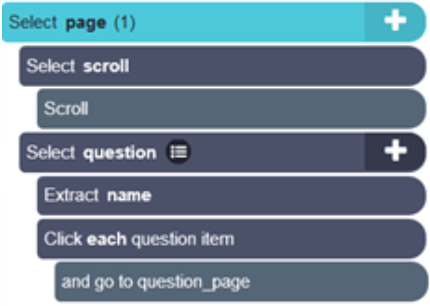

Second method

The second method is simply an all-in-one scraper. It must go over every question, click on the link and based on a template go over every URL and scrape the answers. The following scraper shows how this works

- selects the webpage you want to scrape

- For this one we select the box in which the “infinite” scroll works (the same as point 7 for the previous scraper)

- Will scroll in the selected box

- With this select, we select the question (which contains a link on the actual webpage)

- Extracts only text, in this case the question

- Clicks on every item we selected with the number 4 command

- Opens up a new page in our scraper, this enabled us to make a new scraper that uses the HTML of a different webpage and will be specific only for that webpage

So now we are on the same stage with the 2 methods, this is where our problems started. We tried 3 different methods which all ended up with the same results. All the methods had slight variations which are not explained because the results didn’t change. An example of this is, changing the select command to the relative select command, the relative select command enables you to tie selections together. This will alter the way the data is extracted.

First method

The most straightforward method was to just select the answers with 2 select commands, one for the question and the other for the multiple answers with the following scraper.

But a (recurrent) problem emerged

In our preview next to our question (foto above), no data could be seen where our answer should have been. When we used this scraper, the data wasn’t extracted how we wanted, it was messy (we will later explain what we mean by this). This was done using method 1 one from the previous section.

Second method

The second method consisted of first selecting the box (as we did for the scroll command) in which the answers were. After that, we selected the question and made a “relative select” command to link the answer to the question. Again, the extracted data was not right in our Excel/CSV document. This was done using method 1 from the previous section

Third method

The previous methods tried to put all the answers in one cell next to the question. With this method, we tried to make the answers appear next to each other in separate columns (next to the question) in the Excel/CSV document. This was done by using method 2 as this would give us a new template to work with. In this case the first column is not filled with the “question column”, so all answers would be able to go next to each other. But this also didn’t work out as the data was again not right.

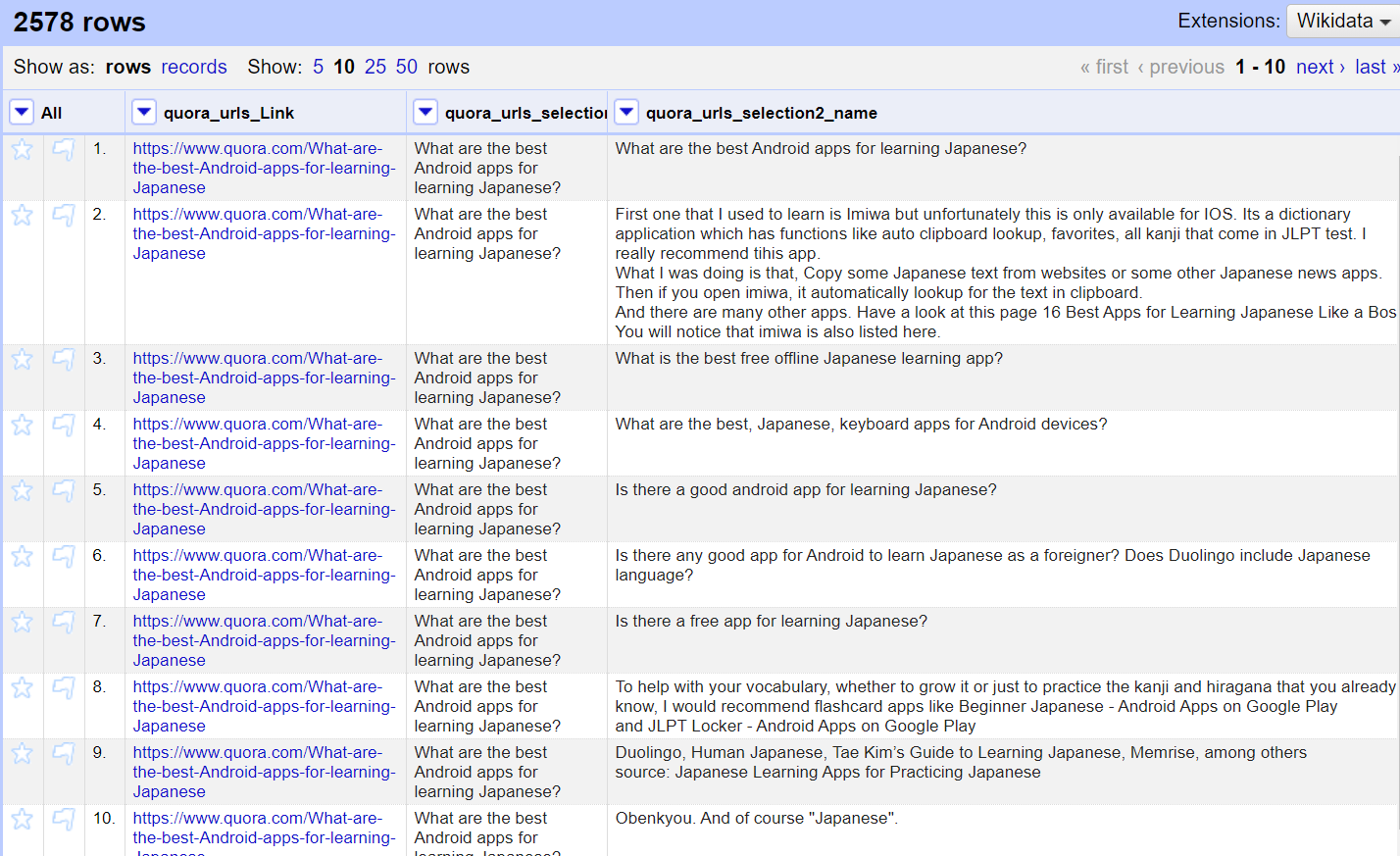

Outcome

Even if we did scrape the links and know how each command worked, we couldn’t make any concrete conclusions in the end. Every time, the extracted data was not correctly displayed and therefore impossible to use. The following picture is an example of this messy data opened in OpenRefine; as we can see, in the first and second column, the very first question that was extracted, is used multiple times. This shouldn’t be the case as the first question has only 4 answers (we counted these manually). The answers of the following questions are displayed next to the first question which tells us this data can’t be used for further conclusions.

Conclusion

Lastly we will discuss what we would have done if everything happened correctly. If we were able to scrape these reviews from Quora correctly, we would have continued with a text analyzing program. In this step the purpose was to sort the reviews into categories by name of application with Openrefine. Followed by analyzing all the answers with a program and sorting them into the “good” and “bad” applications by recognizing certain key-words in the answers. After that, we would have used Tableau to organize this data and make concrete conclusions and a better looking overview of our scraping.

Sources

We chose to store our sources making use of the free and open-source reference management software ‘Zotero’. You will find a list with all the sources read for context, background information and the cited ones. In the individual subcollections, divided as Qualitative and Quantitative research, you can find the sources used for that specific part of the research.

https://www.zotero.org/groups/2848291/online_learning_communities/library